Four lessons rich countries learned from COVID-19

After our poll of over 18,000 people across 15 countries on COVID-19 recovery priorities, Katie Tobin reflects on what the public has taken from the pandemic in terms of government spending, human rights and basic services, and global interdependence.

The lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic, over a year after its beginning, are well-hashed. They’ve become almost clichés – “we’re all in this together”, “no one is safe until everyone is safe”, “COVID-19 is a disease of inequality,” etc. But these statements are grounded in truths that the public of the world’s richest countries have come to recognise.

According to recent online polling by YouGov for WaterAid, most people see a connection between the global emergency of COVID-19 and unequal access to basic services and healthcare – and agree that rich countries have a role to play in addressing these root causes. We asked more than 18,000 people in 15 countries1 what they consider to be the priorities for recovery from COVID-19 and avoiding the next pandemic. Here is what we found.

1. The world was not ready – so we had better get the basics right before the next one

The COVID-19 pandemic has made clear just how unprepared the world was for an emergency of this magnitude. Despite SARS, Ebola, HIV/AIDS, and the prevalence of communicable diseases like cholera long after we should have wiped them out, decision makers at global and local levels had neglected to invest in global health systems (including the World Health Organization or country-specific pandemic surveillance teams). Both foreign aid and national governments have continued to underfund essential services like water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) that could have made us more resilient when COVID began to spread.

When the pandemic began, three billion people lacked the facilities at home to wash their hands with soap and water. And in public places, especially in poorer countries, the situation was just as dangerous. Globally, one in four healthcare facilities do not have basic water services, one in ten have no sanitation services, and one in three lack adequate facilities to clean hands where care is provided. How can we expect people to provide and receive quality healthcare without the most basic measure of disease prevention – especially during a pandemic?

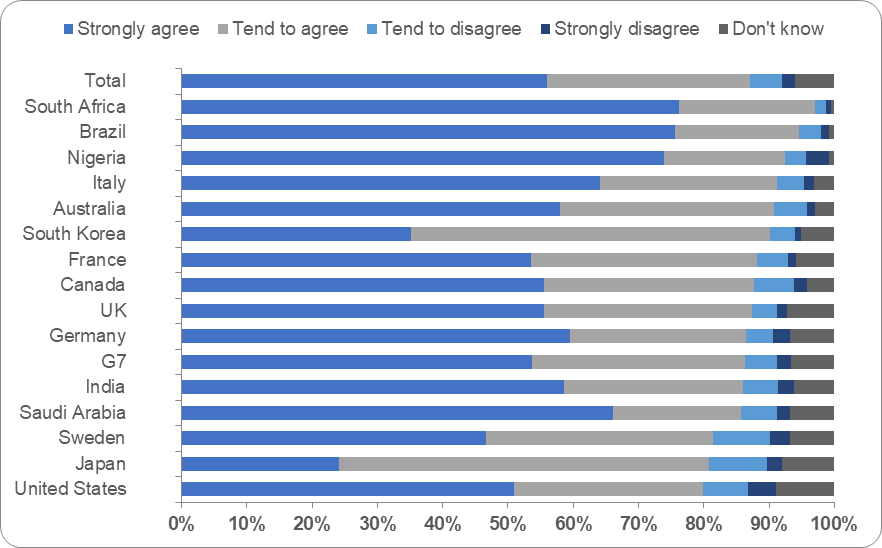

Nearly 9 in 10 people (87%) agree that WASH in public spaces like hospitals and schools should be a core element of pandemic preparedness and COVID recovery plans for people in the poorest places. Countries like Italy and South Africa – who have faced particularly devastating impacts of the pandemic – rank highest in agreeing with this question. In addition, investment in WASH was ranked as the most important prerequisite for combatting pandemics in poor countries.

WaterAid

87% of people agree that WASH in public places like hospitals and schools should be part of the aid G20 nations provide to developing countries, for pandemic preparedness and COVID-19 recovery plans.

2. No one is safe until everyone is safe – so we need global action to protect all of us

COVID-19 was caused by unsanitary conditions in one market in China. It has since claimed the lives of nearly 3 million people, caused “the deepest global recession since the Second World War”, plunged at least 131 million into increased hunger and poverty, reversed decades of progress in global health and pushed 1.6 billion children out of school.

The speed at which coronavirus infections spread from Wuhan to the entire world, and the disruptions in supply chains (PDF) causing disastrous shortages of oxygen, ventilators and PPE showed how interconnected the world is. The economic impacts of lockdowns have also been shared globally (though not equally), amounting to a global contraction of -3.5%, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Rich countries cannot protect their health or their economies while looking only within their own borders. The growing movement for vaccine equity recognises both the moral imperative to share vaccine stock and pause intellectual property constraints, and the reality that the “economic devastation [resulting from uneven vaccination] will hit affluent countries nearly as hard as those in the developing world".

But inequities in other aspects of preventative care are just as important – and have carryovers beyond the specific application to COVID-19. Investments in health and wellbeing, including through fundamental services like WASH, are essential to global efforts to build back better.

More than 8 in 10 people (84%) agree that aid spent on WASH in the poorest countries makes us all safer ahead of the next pandemic.

3. The pandemic made existing inequalities worse – and rich countries need to relieve the debts of poorer ones

Within and between countries, inequalities in access to COVID testing, treatment, and now vaccines have characterised the trajectory of the pandemic and the global response. Gendered patterns of job loss prompt discussion of a ‘shecession’, while in the USA, centuries of discrimination against Black and Indigenous people have resulted in rates of COVID-induced hospitalisation and death significantly higher than in other population groups.

The divide between those who were able to shelter in place without loss of income and those deemed essential workers who had no choice but to put themselves at risk has meant stark differences in rates of transmission and in economic hardship. Continued, drastic inequities in vaccine rollouts threaten to create a twin-track world, in which rich countries begin to recover while the rest of the world sees ever-increasing disparity in human development and basic survival.

International financial institutions and the countries that govern them have taken significant steps to address the economic fallout of the pandemic, in some cases at a scale beyond that of the most recent global emergency, the 2007–8 financial crisis. The recent signal from the IMF executive board of their willingness to consider an allocation of US$650 billion in Special Drawing Rights is encouraging, as are the G20’s institution and then extension of its debt standstill. These measures have significant support among global civil society and world leaders – and, we now know, the public.

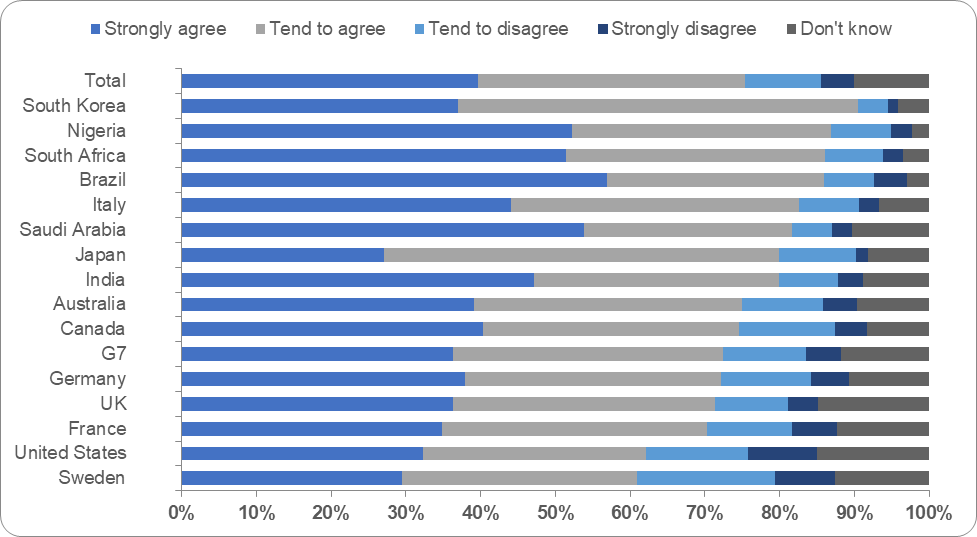

3 in 4 people (75%) agree that debt payments of the poorest countries (including to private sector creditors) should be suspended so that countries can invest more of their scarce resources into essentials like WASH to help fight COVID-19.

WaterAid

3 in 4 people agree that rich countries and private lenders must suspend debts due from poorer governments so they can invest in clean water, handwashing facilities and toilets to help fight COVID-19.

There’s a growing sense that rich countries should take steps to enable poorer countries to respond like they have – with unprecedented injections of liquidity that protect livelihoods, jobs, and wellbeing across societies and our global community. It’s clear that this should include significant measures to free up the cash required to improve access to essential services like WASH.

Action to invest in WASH and support the poorest countries with emergency finance to recover from COVID-19 and prepare for the next pandemic is popular across party lines. This is the case in the politically divided contexts of the UK (host of the G7), Italy (host of the G20), and Germany (the next host of the G7 and driver of EU action).

4. The money is out there, and global cooperation is possible

The creation of multiple successful COVID vaccines at record-breaking speed (and the agreement of government agencies to approve them for emergency use) are a feat of public–private cooperation and a triumph of science. The mind-boggling amounts of stimulus spending mobilised primarily by rich countries – at a level not seen since the end of World War II – show that it is possible to raise and spend money quickly, when leaders determine it’s necessary. (Matching the $1.9 trillion price tag of President Joe Biden’s recent American Recovery Act, for example, could meet a year’s worth of the SDGs financing gap worldwide.)

The cost of providing WASH in almost all healthcare facilities that lack them has been estimated at just $3.6 billion – less than half of the gain in personal wealth of Eric Yuan, co-founder of Zoom, since the start of the pandemic.

Responding to “Which of the following do you think will be the hardest to achieve globally without investment in providing clean water, handwashing facilities and toilets?”:

33% chose “Ensuring everyone has access to the most basic human rights”

19%* chose “Combatting pandemics (e.g. COVID-19) and emerging global health threats.”*This question was asked of adults in Australia, Canada, Japan, Sweden, the UK and the US.

WaterAid/ James Kiyimba

Tigalana Fidah, senior nursing officer, turning the water tap at one of the handwashing facilities at an out-patient, female-friendly sanitation block, Ndejje Health Centre IV, Makindye Ssabagabo Municipality, Wakiso district, Uganda. May 2020.

My grandmother likes to say that, for the generation raised during the Great Depression and World War II, a sense of personal sacrifice and commitment to the greater good was baked in to their daily lives and their understanding of their place in the world. COVID-19 has been the test of younger generations in rich countries, and of the leaders now in power, to live up to the examples of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the post-war Marshall Plan in the efforts they make to recover from COVID-19 and internalise the lessons of the pandemic.

Are we really “all in this together”? We’ll be looking to the upcoming summits of the G7 and G20, and to decisions of the IMF and the World Bank, to find out.

Katie Tobin is Advocacy Advisor – Multilateral Institutions in WaterAid’s global team.

1 Online polling conducted by YouGov between February and March 2021, of 18,635 adults across Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, South Africa, South Korea, the UK and the USA. For the full analysis of the polling, see washmatters.wateraid.org/publications/public-support-wash-resilience.

Top image: Jemima, student in Grade 6, outside the girls toilet with friends (M-L) Bonni and Chanel at their primary school in Rigo District, Papua New Guinea.