Sakhile Khaweka is based in WaterAid’s South Africa office. She works with governments to influence policy on water and sanitation provision, and coordinates projects across Southern Africa.

Day Zero (noun): The day a city or town runs out of water.

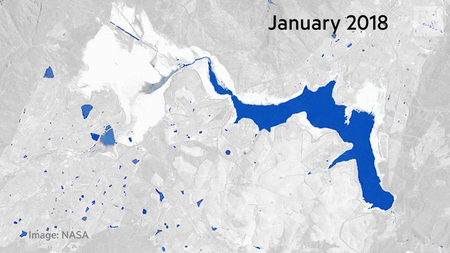

Cape Town's 'Day Zero' was meant to be March 2018. A combination of the ongoing drought, climate change and population growth meant that the city's taps were on course to run dry.

I saw everyone – from elites to ordinary citizens – queuing for water, jerrycans in hand. The situation affected businesses, tourism and the general comfort of the affluent community of Cape Town.

The realisation hit home that you might turn on your tap and nothing come out, and there was genuine panic in the air.

But then, a change came.

Day Zero was pushed back to July, then August, then 2019. International media attention died down. Water levels replenished, and all without major rainfall. So what happened to avert the crisis?

Government intervention was the real game-changer. The regional government of Cape Town (who are responsible for the city's water provision) set up an aggressive campaign to reduce water consumption the moment they realised the reservoirs were drying up.

Monitoring systems were put in place to measure water usage. TV shows, radio programs and posters prompted entire neighborhoods to reduce their consumption to 50 liters a day (to compare, Londoners use on average 164 liters a day). Neighbors were publicly named and shamed for going over their daily quota.

The Cape Town government demonstrated the positive change that can happen when decision-makers get behind a common goal, and the crisis has been averted. For now.

But the uncomfortable truth is that we're at the mercy of the rains, and it's not just Cape Town that's at risk.

A financial crisis?

To mitigate the emergency in Cape Town, water was diverted away from agriculture for domestic use. This may affect food and wine production, leading to job losses and a weakening of the industry. Sectors need to work together to monitor water use in the future.

Rural areas and informal settlements are already living out 'Day Zero', made worse by the floods and droughts that are becoming all-too-common across Southern Africa. Other major cities, such as Maputo in Mozambique, are also facing similar crises. We must learn from the Cape Town crisis and ensure that both regional and national governments provide sustainable water and sanitation to all their citizens – irrespective of wealth or the effect of climate change.

These basic provisions are just one of seventeen 'Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)' agreed to by 193 governments worldwide in 2015. The aim? Putting an end to extreme poverty by 2030.

With 785 million people still living without clean water close to home, and 2 billion without a decent toilet of their own, the goal is ambitious. Progress is slow, which is why we need the public (and sector-specific organizations) to pressure governments to stick to their 2030 deadline. High-profile events, such as the SDG review in July 2018, are the perfect chance to do so.

Without serious action from governments, 'Day Zero' will become a common occurrence. In the meantime, we'll just have to pray for the rains to come.